‘This has become a dumping ground, lads’. We have been in this village all our lives and now we are expected to share with that lot, we don’t even know them.’

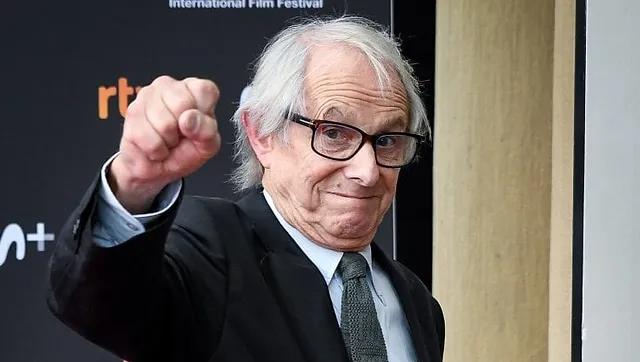

These lines of dialogue set the background of The Old Oak, the latest, and possibly last, film of veteran British director, Ken Loach. The dumping ground is an ex-mining village in north-east England, and ‘that lot’ is a group of Syrian refugees being settled in the UK after fleeing war in their homeland.

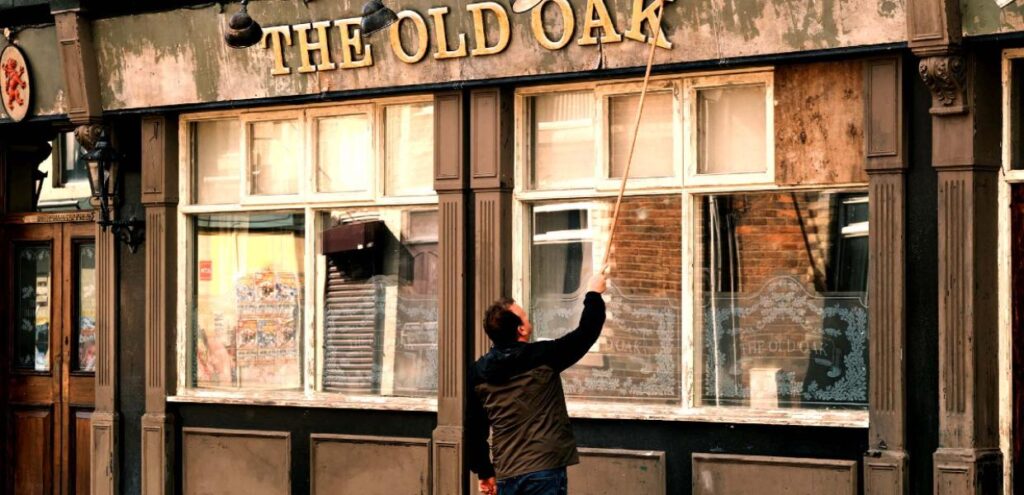

The film is set in the year 2016. A year earlier, the UK government had decided to take in 20 000 Syrian refugees over a period of five years and a group of refugees has been sent to live in the village. The village residents are angry. It is they, not the politicians in faraway, rich London, which must deal with the consequences of that decision. No one ever asked them. Life in the village is already hard. Poverty levels are high. People are struggling to cope. Public services are overwhelmed. Even the village school has closed. The only place where people can meet is the local pub, The Old Oak.

Many villagers support Brexit (the UK leaving the European Union) because they believe that there are too many foreigners in the country. Now they must accept more people from outside. It is the last thing that the village wants. ‘We can’t look after our own,’ says one of the residents. The villagers feel that they have nothing left to give, especially to people they do not know, immigrants with whom they have nothing in common.

Ordinary people being abused by those who have power is a theme of many Ken Loach films. Unfairness caused by this abuse leads to conflict between otherwise decent people. Victims turn on other victims. The innocent are hurt, while the powerful remain largely unaffected and indifferent.

In the film, while it seems that the villagers and refugees are very different, in truth, they have much in common. Both groups are victims of the abuse of power by the authorities under which they lived. Both have lost their way of life. For the Syrian refugees their loss is clear. To survive, they fled a war zone, leaving behind people, places and possessions that they loved. Now they find themselves in a strange land with different traditions. The colours of people’s faces are different. The language is familiar but spoken at a speed and in an accent that make it unrecognisable from that heard or read on TV, radio and social media. It’s also cold. The sky is dark and the sun hides. Their future is uncertain. They are afraid.

The village residents were not moved thousands of miles, but they have also lost their livelihoods. We never learn its name, but the village is one of many across the UK that has never recovered from the brutal closure of the coal mines by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government in the 1980s. Loach’s decision to set his story in a former mining village is deliberate. 2024 marks the 40th anniversary of the beginning of the bitter year-long strike by the miners to resist pit closures. The strike failed. The pits were closed, taking with them the well-paying jobs that gave dignity, respect, and the promise of a better future for the next generation. The villagers war was not one of bombs and bullets. They fought and lost an economic war of profit and loss. The Syrians refugees left behind their livelihoods to seek prosperity elsewhere. The people of the village were left behind when their livelihoods and prosperity went elsewhere.

The 1984-85 miners’ strike is documented in photographs in the Old Oak pub. Photography is the passion of one of the refugees -Yara a young Syrian woman. The photos of the villagers’ struggle to save a way of life is the connection with the struggle of the Syrian refugees to make one. While some cannot overcome their fears of those who are different, Loach’s film shows faith in human resilience. Endurance, strength and honesty, in English myth, are symbolised by the oak tree after which the pub is named. As refugees and villagers learn more about each other, the refugees are no longer ‘that lot’ but human beings who, like the villagers, share a determination to survive.

Many of Loach’s films warn of the consequences of the powerful losing sight of the people whose fate they control as human beings. In one of his early films Cathy Come Home (1966), a mother tries desperately to keep her children after losing her home following her husband’s injury at work. The interest of the authorities is to protect the children, but rather than help the mother find somewhere to live, they take the children from her. Some 50 years later, in I, Daniel Blake (2016), Loach explored how the UK’s welfare system is used to punish poor people for the crime of being poor. To ‘protect’ public finances from the lazy who exploit the system, help is denied those who need it. Deterrence for the feckless becomes cruelty for the needy.

Not only governments can lack humanity. In The Rank and File (1971), management and unions both conspire to keep ordinary workers in their place. More recently, Sorry we missed you (2019), shows the false promise of flexible working made by the gig economy and ‘zero-hours’ contracts. In reality, the consequence of insecure income, no sickness or holiday benefits can be the breakdown of working and family life. Strict religion can also be a system of control and barrier to happiness as Loach shows in Ae Fond Kiss(2004), a story of the son of Pakistani immigrants falling in love with a Catholic school teacher. Families, too, can be cruel. People who just don’t fit in can find themselves bullied by schoolteachers and family as Loach showed in Kes (1969).

Ken Loach has, for almost 60 years, used his films as social commentary. If The Old Oak is his last film his voice will be missed. He has warned how poverty, insecurity and fear can be used by the powerful to control the weak. His message is that such exploitation happens when we forget or ignore that those who suffer are ordinary people, who often through no fault of their own find themselves vulnerable. His solution is human solidarity and kindness. After all, we only have each other.