Peter Jackson is Professor of Global Security at the University of Glasgow. He self-identifies as a man of the Left and a critical defender of the European ideal. His research interests cover the fields of Strategic Security Studies, Intelligence and Security Studies, International History and Modern France.

Many analysts argue that the rise of nationalists such as Trump, Orban, Bolsonaro, the rise of China and the fall of American power create an explosive mix similar to that of the eve of the two World Wars. What is your position on the issue?

I do not know if the two world wars are the best analogy, but at the moment we are experiencing a series of different dynamics, even one of which is enough to destabilize the world system as we know it.

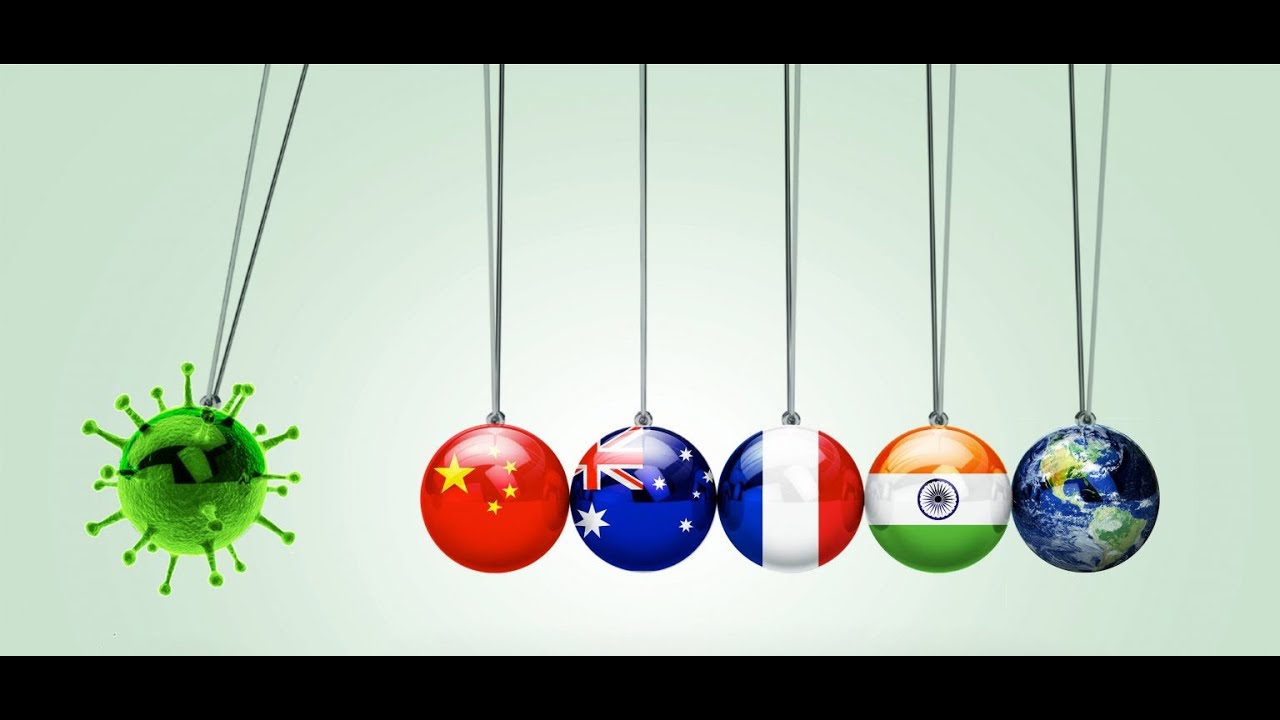

One is the rise of nationalism as you mentioned, which I think is a reaction to the crisis of the liberal internationalist capitalist order as we have known it. China’s rise as a world power, a building block of the global system for the past twenty years, is another destabilizing factor and is being accelerated by two developments. First, the current Chinese leader. Xi Jinping is more confident, more determined, more unapologetically nationalist than all his immediate predecessors. Secondly, I believe that the Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated China’s rise, as the Chinese have been able to tackle the virus much more effectively than the capitalist forces of the West, which are much more exposed to the pressure of popular movements. As a consequence of the latter, the pandemic is to a much lesser extent a destabilizing factor for the Chinese economy than for the European and American economies.

These factors have thus accelerated the emergence of China as a challenge and as many think as a revisionist force within the system. China, as most analysts would agree, is no longer a status quo force. It wants to assert itself regionally and globally, for example in Africa and to a lesser but significant extent in South America, which for over 150 years the US has successfully maintained as its own “backyard” under the Monroe Doctrine.

Therefore, all these factors together, the crisis of liberal capitalism, the rise of China, the pandemic are combined at the same time into something that could develop into a new form of radical instability if not handled properly. An instability which, in my opinion, was accelerated by the strange, idiosyncratic and contradictory policy of the Trump administration, which on the one hand it recognized China as a problem while on the other hand, given its isolationist reflexes, it did not prioritize building networks of alliances, tha would help it engage with China from a position of strength.

These are the challenges at the international level, but I believe that before the United States and Europe thinks about going forward and meeting these challenges head on, they need to reorganize and address the issues left behind over the past 25 years, since the end of the Cold War, especially the rise almost hegemonic status of the neoliberal economic policies. Policies that alienated many who lost out of the whole process of globalization and neoliberal models, which pursued labour where it was cheapest and ran down some of the basic principles of a more communal economic model that existed in places like Britain or the United States and elsewhere. As a result, nowadays in Britain, where I live, there really don’t make much anymore. There is a tech industry and there is a car industry, but we have to keep in mind that Britain was once considered the cradle of the industrial revolution and a global factory.

As a result, you have regions within the UK that were traditionally the backbone of the manufacturing economy (coal mines, steel, etc.) and many of these economic activities which nowdays have disappeared, with all the painful consequences that this whole procedure entails. And the logic of the economic model behind Brexit I have to tell you was just to get rid of it all an hour earlier and move on to a service economy.

Coming back to the issue, I would say that these policies have alienated much of society, creating a big problem for the functioning of the economy and democracy, a problem that is being solved through two possible paths. The one says “it’s really complicated and difficult to fix, but we have to pursue a long-winded and collective course” while the other is presented as an easy solution and its pursuit is limited to regaining dominance, regaining sovereignty against foreigners.

So what you are saying is that in such a case right-wing nationalism was presented as a solution for them?

Exactly, although in the long run it is not a solution of course. We have seen such instrumentalization by the Trump administration, through a return to deep-rooted and popular political traditions within the United States, an intense flirtation with isolationism. “Let’s make America great again,” “Let’s look at our interests again,” “Let us stop working for the benefit of Europeans, Koreans, Chinese”. Τhat dimension of the Trump administration, however, undermined the need to deal with the rise of China collectively, creating a sense in Beijing and Moscow that the West is entering a phase of weakening. So as long as the West cannot restore confidence in its own version of democracy, it will be difficult to compete with China’s size in the international order.

But what do you think is the first challenge for global security as the post-coronavirus world emerges? Aside from what China will do, isn’t the US obsession with the superpower monopoly yet another danger?

First of all, it would be absurd not to expect the American president not to have the national interest at the center of his foreign policy as he sees it. The question is how he perceives this interest. Does he perceive it as the leadership of an international order that attributes due value to a set of principles and values or has a narrow-minded perception that wants their own interest above all else? The way states respond to the pandemic is very interesting, because it proves that in most cases a nationalist, selfish prioritization of the “I first” type prevails in every state. The United States was such a case under Trump, and while a change of president means a lot, it does not mean a sharp return to the pre-Trump era, much less at the beginning of the first decade of the 21st century.

Of course, on the other hand, the EU, which has chosen a more collective way of responding to the crisis, has completely failed and has been rightly criticized. It will take a long time for the European Commission to first come to terms with its failure to secure enough vaccines and set up a mechanism for their distribution and then their futile confrontation with the UK. I’m not a friend of the conservative government in London led by Boris Johnson, but the EU has not impressed in any way. Things may get better along the way but for now the impression is that the EU has given in to the anxiety of finding a quick solution to vaccination and it has cost it.

There is a belief in Greece that this is another failure of the EU, in a long list that includes the economic crisis of the eurozone, the case of the European management of Grexit, the Brexit case.

This is true, if you focus on specific issues you can point failures, although in some of the bigger issues you can find successes in my opinion.

Of course, if I was viwing things from Athens, I would have a different impression from the way I see things in Glasgow and I fully understand the criticism of my Greek friends that is more lively in terms of the virtues, attractiveness or even usefulness of the EU than we are in Scotland, where I think we are very idealistic and unrealistic about the whole thing, which has to do mainly with the experience of Brexit and wrenched out from the EU, where the vast majority of Scots voted to stay within .

My next question concerns the independence of Scotland. Could you talk about the general climate in Scotland, provide us some context on the issue and also talk about the struggles that are currently happening in Scottish society?

It is quite obvious that the combination of Brexit, in relation to the referendum in Scotland in 2014 as to whether our country will become independent, with one of the main arguments then being that Scotland would not enjoy the benefits of staying in the EU if it decided to leave, is the key that will help us understand what is happening.

“No” prevailed in the independence referendum – I personally voted to stay in the UK – although by a small margin, 55-45%. And two years later, against the will of 62% of Scots, we are now outside the EU. This experience is a very important factor in building support for independence. It is not necessarily accompanied by enthusiasm for the EU, but I think it’s driven home amongst many people a realization that in a union of four nations which is dominated by one bigger nation, the English, versus the smaller ones, the small nation like Scotland (which is only 8.1% of the population of the UK), will always be hostage to the fortune of English voters.

And then there is certainly a perception amongst the Scottish intelligentsia that Brexit was an English nationalist project. And there is a sense that Scotland turned its back on its own nationalist project of independence in 2014 as a reaction to British nationalism, only to be dragged out of the EU in 2016. This, combined with the Johnson administration’s spectacular pandemic mismanagement since last March and the confidence that Nicolas Stargeon seems to inspire as prime minister are the reasons that generated a lot more support for independence. But it is not so much the expectation that we will be better off outside the Union as the fear that things will get much worse inside.

The one element capable to reverse this trend is the fact that the only thing the Johnson administration has got right in the UK is the vaccination, which is moving relatively quickly and may, as some say, halt the trend towards independence. I do not think that will happen, in the last fifteen polls independence has taken the lead, especially in the younger generation. Especially since each younger generation, every younger class of young people that come to adulthood are more and more enthusiastic about independence than the previous one.

Why? What is the main reason?

Honestly, I do not know. I have begun to conclude that there is a perception that the Scottish model of nationalism is more open-minded, more inclusive than the English or British.

Do they see a more progressive definition of nationalism?

Yes exactly. And with more social consciousness than the English version. On the other hand, of course, my initial specialization had to do with Europe in the two world wars, and it is not possible to study this historical period without being fundamentally skeptical of any version of nationalism. And this, because after all, nationalism is about “who is inside” and “who is outside”, defining yourself in relation to what you are not, just to produce a sense of community.

The Scots say that is not the case, Scotland welcomes refugees, welcomes and needs immigration, as it has an aging population reminiscent of the German case.

In any case, every line of younger Scots is increasingly in favor of independence, so if I were to bet I would not bet that Scotland would remain in the UK.

Then, of course, the question arises as to what this would mean for Scotland socially, politically, economically. Let us not forget that 62% of Scotland’s trade is with England, so if Scotland leaves the Union and joins the European single market it will have trade borders for 62% of its trade. This can be offset by other dynamics, such as increased trade flows through the single market, also with inward investment for access to the single market that would otherwise go to England, there are arguments that Scotland may bloom. Of course, there are arguments on the other hand, such as the fact that a lot of exports are countedd as scottish but they are managed out of London, for example most Scotch whiskey is traded oit of London, even though it comes from Scotland.

And as a big fan of “Big Lebowski” I would say that there are a lot of ifs, a lot ins and outs in the whole issue. So I would say that although I do not know how I would vote in an independence referendum, I would not bet against Scotland becoming independent in ten years at the most.

Given your interest in modern-day France, how feasible is it for France today to live up to its role as a major European power? For many years, many EU countries have been waiting for Paris to become a counterweight to Berlin.

There is a kind of inherited contradiction in France’s geopolitical posture. On the one hand, it seeks to use the EU as a vehicle for the exercise of power internationally in diplomatic, political and, above all, economic terms. On the other hand, and given the most classic power projection tools such as aircraft carriers, troop numbers and strategic strike forces, its natural collaborator is Great Britain.

That is an interesting contradiction in the France’s position, it looks to the EU for power, especially “soft power”, while it looks to Great Britain to maximize its ability to project more classical, military power through a variety of arrangements that have been negotiated with the British, especially since 2010 and the Franco-British security and defense cooperation. This opposition is intensified, I think, by the political tradition of Golism, which insists on French strategic independence through the country’s nuclear power.

But that is not the only contradiction. Another contradiction is the fact that France for a long time has to play on the legacy of its imperial presence in Africa through organizations like the International Organization of the Francophonie (OIF), where as such narratives are not as attractive as in the past. Imperialism – even at the level of popular culture – is much less accepted as a value than it was, not in the distant past, but 25 years ago.

France, however, is still present in Africa.

Of course, they are trying to maintain their influence, but I think that influence has been in a recession for a long time, events like the Rwandan genocide and the ensuing African wars accelerated that trend. However, you are right that even in France they see their presence in Africa as one of the pillars of their global voice.

The presence of President Macron, who promised to make the power of revitalization in Lebanon fruitless to this day, is for some a sign of the recession in which French power has entered.

The pandemic will further complicate matters, and this is because it has forced great capitalist powers like France to retreat on themselves, we see a tendency of introversion. The way they will react to the damage caused by the pandemic economically, politically, culturally is still the most interesting.

If we look at the end of the last major global pandemic, the Spanish flu in 1918, its end was accompanied by an explosion of energy and creativity in political culture in the US and Europe, which lasted unabated for three to four years. And not only in terms of politics and diplomacy, but also in terms of economics, the tragedy of the Crash of ’29 was in fact so catastrophic because the 20s, the roaring 20s until then were considered a golden period. So a number of questions arise, such as what will be the future of world trade, what will happen from now on? For example, Trump challenged world trade as we have known it since the end of the WW2. Surprisingly, such a development would hurt China, which is dependent on world trade. We will see what happens next and the implications for the global system.